Entry Nineteen: High North, High Tension

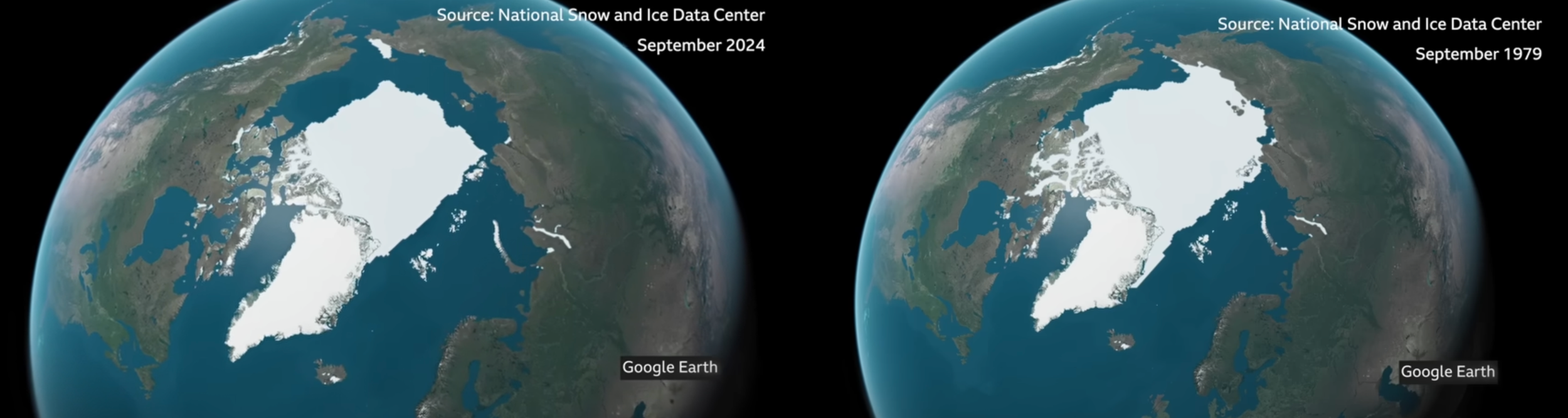

There are two satellite images of the Arctic that refuse to leave my mind. One from 1979. One from 2024. They look almost identical at first glance, the familiar white arc at the top of the world, clean and abstract, like a graphic pulled from an atlas. But then you look longer. You notice what is missing. You start tracing the edges. And suddenly the absence becomes impossible to ignore.

Since 1979, the Arctic has lost approximately 2.6 million square kilometers of sea ice. That number is so large it barely registers. We are bad at scale. So here is another way to say it. An area roughly the size of Argentina has vanished. Not relocated. Not transformed. Gone. Converted from solid to liquid. From presence to absence. Nothing dramatic announced it. No single moment. No siren. Just a slow retreat, year after year, pixel by pixel.

We often talk about melting ice as a future problem. Something approaching. Something still abstract. But the Arctic is not melting. It has melted. What we are living with now is the consequence phase. And consequences do not arrive quietly. They arrive wearing the language of opportunity.

Today, 97 ships pass through Arctic shipping routes each year. Ninety seven. A number that sounds modest, almost cautious. Especially when compared to the approximately 13,000 ships that move through the Strait of Gibraltar annually. The comparison is often used to reassure us. To suggest that Arctic shipping is still marginal. Experimental. Controlled.

But the math is not subtle. As ice disappears, routes open. As routes open, traffic increases. As traffic increases, geopolitical tension follows. Nobody truly believes the number will remain 97. That number exists only because the ice still exists. And the ice is disappearing.

2024 - 1979. Source: National Snow and Ice Data Center

This is where the language shifts. Melting ice becomes efficiency. Absence becomes access. Collapse becomes a corridor.

What is happening in the Arctic is not accidental. It is not a side effect. It is the logical outcome of a system that treats disappearance as usable space. The ice retreats and we rush in to occupy what it leaves behind. Not to mourn it. Not to slow the process. But to extract value from its absence.

We tell ourselves stories about inevitability. About global trade. About economic necessity. We say these routes shorten distances. Reduce fuel costs. Improve efficiency. We speak as if efficiency were a moral good, as if it exists outside of consequence. As if shaving days off a shipping route justifies the erasure of an entire ecosystem.

The Arctic is no longer remote. It is contested. Militarized. Mapped not by seasons but by strategy. Nations posture. Corporations calculate. Everyone watches the ice not with concern, but with interest.

This is why the Arctic feels tense now. Because it has become legible. Because it has become useful. Because it has stopped being an untouchable void and started behaving like infrastructure.

Climate collapse is often framed as tragedy. But tragedy implies loss without gain. What we are witnessing in the High North is something more disturbing. Loss that produces profit. Disappearance that creates opportunity. A feedback loop where destruction becomes incentive. The ice melts. Ships arrive. Emissions increase. The ice melts faster.

We pretend these are separate issues. Climate. Trade. Security. But they are the same story told with different vocabularies. The Arctic is not destabilizing because of conflict. Conflict is emerging because the Arctic is destabilizing. And through all of this, the images remain deceptively calm. Satellite photos. Clean lines. Blue water replacing white. It looks almost beautiful. That is part of the danger. The collapse photographs well. This is how normalization begins. When loss is rendered smooth. When transformation looks like progress. When maps update quietly and no one asks what disappeared in the process.

We are trained to look for villains in climate narratives. Oil executives. Politicians. Corporations. And they exist. But the deeper failure is cultural. We have accepted the idea that once something is gone, the only remaining question is how to use what remains. That is the real tension in the Arctic. Not between nations, but between worldviews. One that sees disappearance as a warning. And one that sees it as an opening.

The shipping routes are not the problem by themselves. They are a symptom. Evidence of how quickly we adapt to loss when adaptation benefits us. Evidence of how little time we spend grieving before we reorganize. Two point six million square kilometers. Argentina. That should stop us. It should slow us down. It should introduce hesitation. Instead, it accelerates planning. We like to say we are unprepared for climate change. But in the Arctic, preparation is exactly what is happening. Not preparation to prevent collapse, but preparation to exploit its aftermath.

The language gives us away. We talk about ice free summers as milestones. About navigable waters. About new corridors. Rarely do we talk about what it means to live in a world where the top of the planet is no longer frozen. This is not an endorsement of stagnation. It is not nostalgia for a static world. Change is constant. But there is a difference between change we endure and change we engineer through neglect.

The Arctic is changing because we allowed it to. And now we are reorganizing around the damage as if it were neutral terrain. This is where art enters the conversation, not as decoration or awareness, but as resistance to normalization. Because once collapse becomes infrastructure, it becomes invisible. Ghosts of the Ice exists precisely because numbers alone are not enough. We can recite square kilometers lost. We can compare ship counts. We can chart routes and emissions. And still, the loss remains abstract. Informational. Something we know without feeling.

I am not interested in documenting opportunity. I am interested in holding space for absence. In refusing to let disappearance become background noise. In forcing a pause where the system demands acceleration. The Arctic does not need another efficiency analysis. It needs witnesses. People willing to stay with the discomfort of loss long enough to resist turning it into advantage.

High north. High tension. Not because the region is volatile, but because it reveals us. It shows how quickly we adapt to destruction when it benefits us. How easily we confuse access with progress. How comfortable we have become standing on the edge of disappearance, already planning what comes next. The ice is not opening a route. It is leaving. And what we do in response will define far more than shipping lanes.

As we all carry responsibility for what is happening on this planet, I cannot shake how stark the contrast has become between the pace of environmental collapse and the pace of wealth accumulation at the very top of our economic hierarchy. In the last few years, the world’s billionaires have never been richer. Their combined fortunes now exceed $16 trillion, an amount greater than the annual economic output of most countries, and up by around $2 trillion in a single year. Some of the richest individuals on Earth saw their own net worth jump by tens of billions in 2024 and 2025, adding wealth at a rate that outstrips any measure of shared human progress. While people struggle with rising costs, climate disruptions, and shrinking opportunities, this tiny class has grown more powerful and more insulated from consequence.

And that brings me to a question I find impossible to ignore. When I think of the mega-billionaires, the Musks, the Zuckerbergs, the elite whose scale of wealth eclipses nations, I think about their doomsday bunkers. The extravagant shelters built in remote corners of New Zealand, in gated enclaves in Hawaii, designed so that if the world genuinely fell apart, they would be safe. Safe from what, exactly? Who would be left outside when the doors close? Who will provide for them? Who will serve them? If your personal security team is twice your size, how will that person be fed once the bunker is full? These questions are not rhetorical. They expose a worldview in which the endgame is retreat rather than repair.

We have been conditioned to believe that the richest among us are leading us toward a better tomorrow by investing in ambitious futures like colonizing Mars or building technologically perfect lives elsewhere. The promise is seductive: a multi-planet species. But the reality of those worlds, if they were ever reachable, is inhospitable by design. Radiation that will kill you long before you ever harvest a potato, gravity too weak to build muscle, environments that demand more technology than biology can withstand. Mars is not a Plan B. It is a monument to distraction and fantasy. Meanwhile, right here, we have oceans, plains, forests, breathable air. A planet that was once assumed to be resilient and now is not.

This is the fundamental lie: that survival can be outsourced, that intelligence lies in withdrawal rather than stewardship, that prosperity means isolation rather than shared responsibility. When someone tells you that the future is off-planet, or that economic success means hovering above the consequences, ask whose future they are talking about. Because it is not yours. Not really. Not in the soil that grows your food, not in the water that quenches your thirst, not in the air that carries the songs and stories of your life.

Earth should be priority number one from every point of view. Not a backup plan. Not a resource dump. Not a laboratory for human ingenuity untempered by humility.

“Mars is not a Plan B. It is a monument to distraction and fantasy.”