Entry Eight: The Quiet Edge

Every journey has its pauses, the moments when you must step sideways to move forward. Before I write about the north again, I want to talk about the southwest, New Mexico, to follow a different kind of light. I visited the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe and later rode horseback through the canyons near Ghost Ranch, tracing the ochre cliffs and violet shadows that once became the backgrounds of her paintings. Visualizing the silence that shaped her vision.

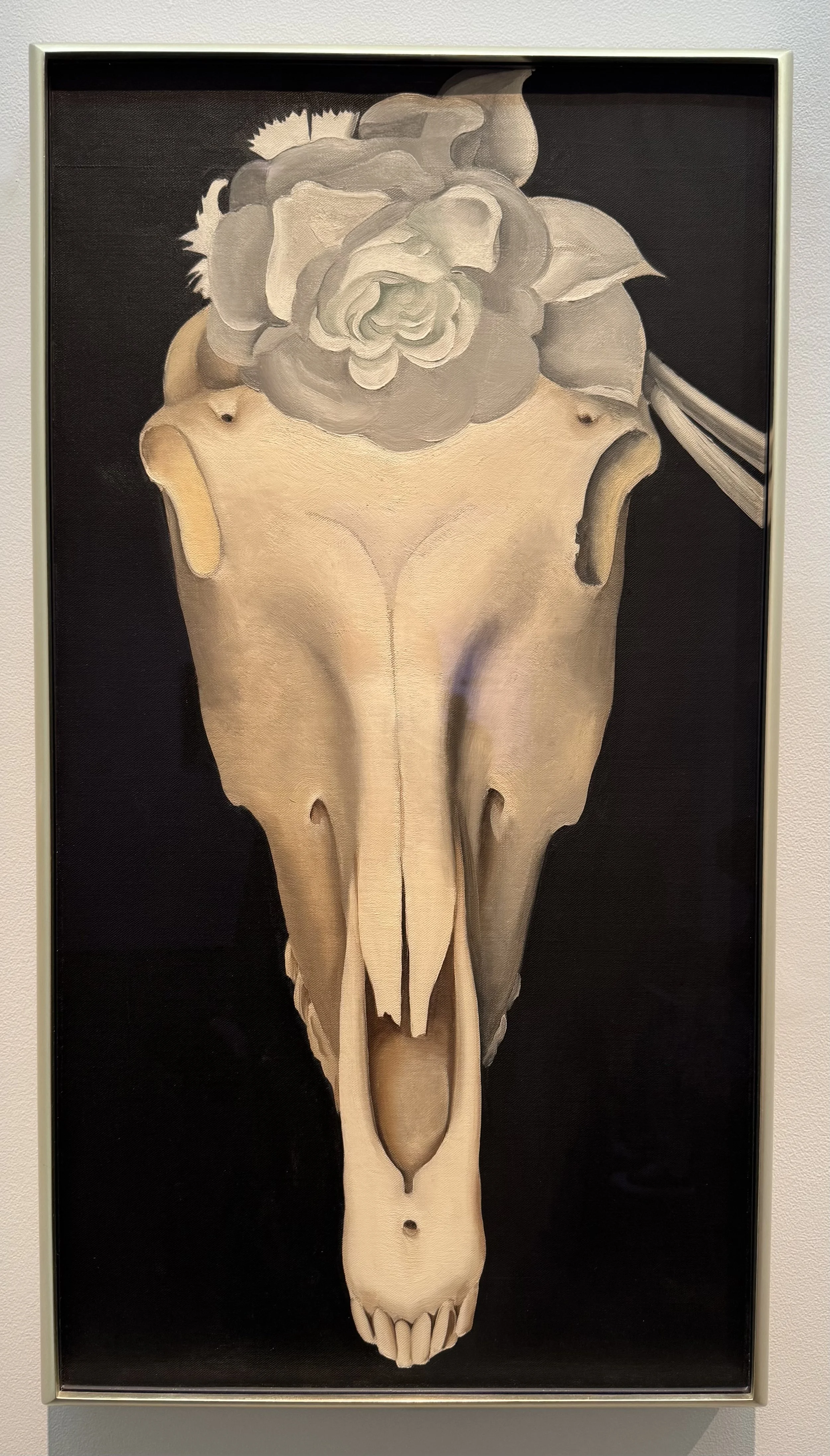

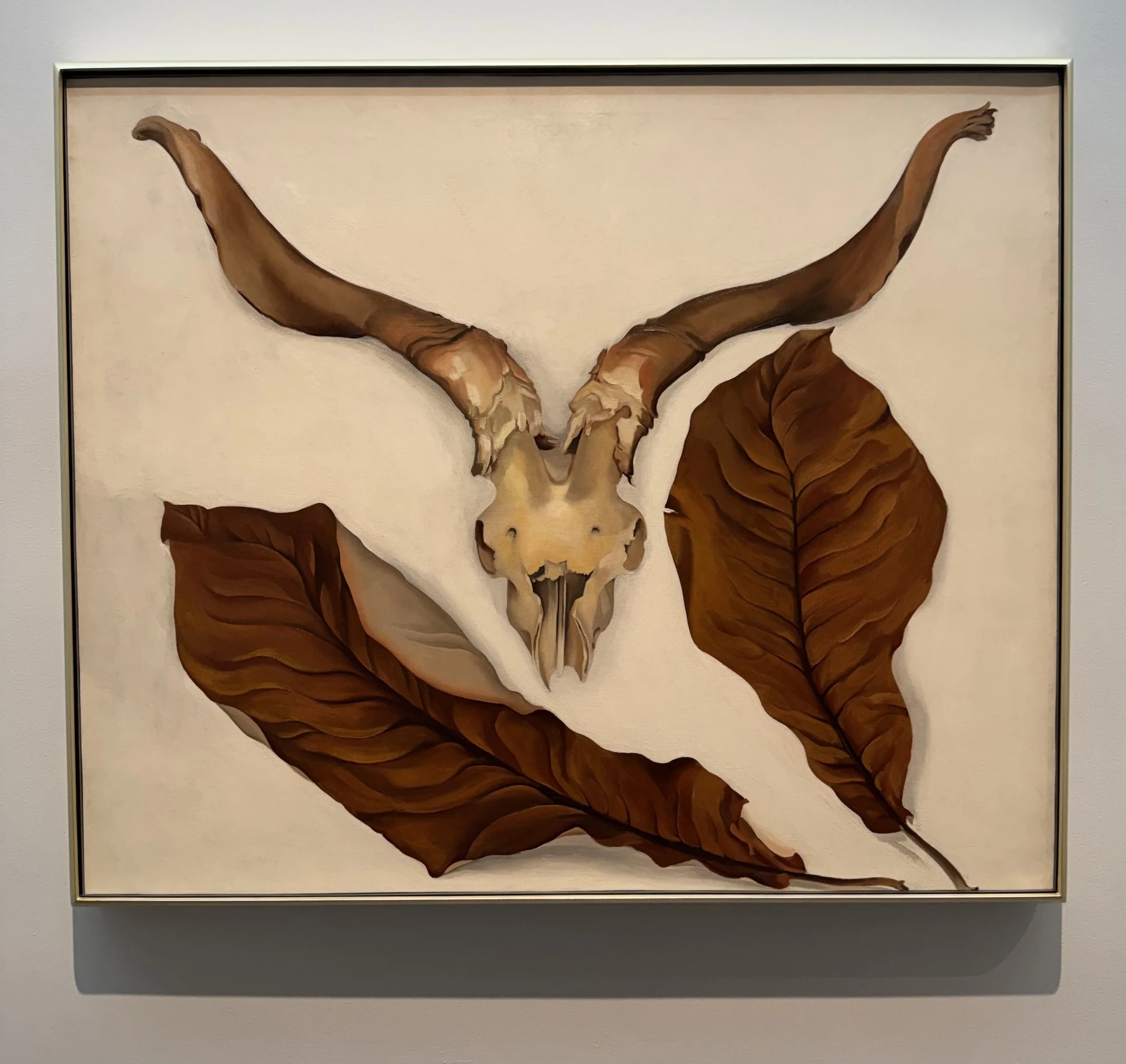

What struck me was how O’Keeffe painted not what she saw, but what she felt while seeing. Her desert was not a landscape but an interior space, a geography of solitude and surrender. Standing among those cliffs, the air dry and still, I could almost sense the rhythm she found, the pulse between vastness and intimacy, the way she allowed emptiness to breathe on the canvas.

O’Keeffe remains one of the most singular voices in American art. Her discipline was devotion; her independence, a kind of rebellion. She left behind the noise of New York to live among bones and sand, painting what most people overlook, the inside of a flower, the curve of a skull, the infinite line of a desert horizon. What people called simplicity was, in truth, precision. She stripped the world to its essence and somehow made it larger.

What moved me most, though, was her persistence. In her later years, when her eyesight began to fail from macular degeneration, she did not stop working. Her vision diminished, but her hand remembered. The movement itself became the art, her body carrying out what her eyes could no longer guide. The motor memory of decades at the easel took over, like a musician playing a song long after forgetting the notes. There is something deeply human in that, the idea that art is not only seen, but felt through muscle, breath, and instinct.

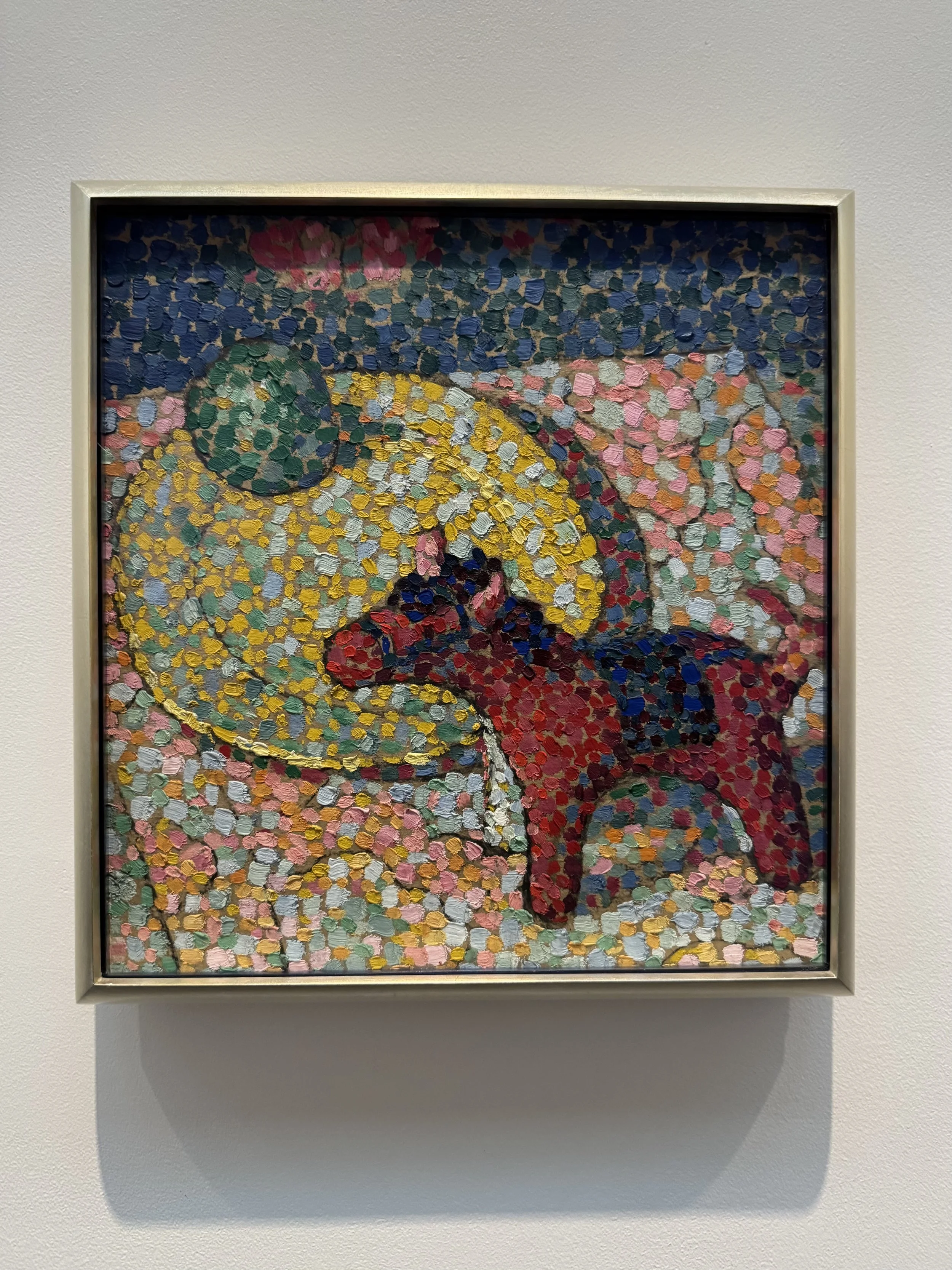

It reminded me of Kandinsky’s Composition VIII, a work built not on representation but vibration. Kandinsky painted what sound looked like; O’Keeffe painted what silence felt like. Both searched for the unseen architecture of emotion. When O’Keeffe’s sight faded, she began to paint from the same invisible space Kandinsky once described, a kind of internal geometry, where memory and motion meet.

Riding through Ghost Ranch, I kept thinking how her desert and my Arctic are not opposites, but reflections. Both are landscapes stripped to their essentials. Both ask for stillness. Both tell you what remains when everything else has been taken away. For O’Keeffe, the desert was a world reduced to bone and color. For me, the Arctic is a world reduced to light and ice. Each, in its own way, speaks of endurance and the thin line between presence and disappearance.

This detour reminded me that inspiration doesn’t always come from moving faster, sometimes it comes from standing still long enough for the land to speak back.

PLEASE NOTE:

Things have changed. You may have noticed that I have concluded and deactivated all my social media for now. I can vote, and I can decide where I spend my time and energy. I choose not to enable billionaire czars who profit from outrage and distraction.

Social media has become less about community and more about control. It thrives on division, turning people against one another, race against race, gender against gender, belief against belief, while convincing us we are connecting. It’s exhausting, and it’s designed to be. The more frustrated we become, the more attention we give.

I believe the climate, both real and political, needs to be better. I believe in art, empathy, and honest dialogue. But until this digital landscape changes, my work will live here on my own website.

“I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn’t say any other way, things I had no words for.”