Entry Ten: The Silent Page

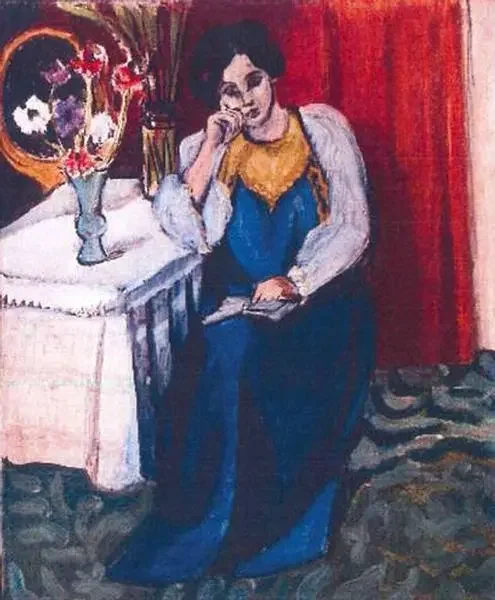

This is the third and final painting in the constellation of lost works guiding Ghosts of the Ice. The storm came first, roaring through Rembrandt. Then Klimt, whose Philosophy dissolved in fire. Now we arrive somewhere quieter. A girl seated in profile, absorbed in a book, sunlight touching her white dress and yellow accents. A moment so ordinary it becomes extraordinary.

Henri Matisse painted Reading Girl in White and Yellow in 1919. Europe was recovering from the First World War, rebuilding its voice, its cities, and its equilibrium. Matisse responded not with grand declarations but with rooms full of serenity. Throughout this period he returned again and again to interiors, windows, chairs, the slow pulse of domestic life.

Reading Girl in White and Yellow (1919) by Henri Matisse

He had spent the last decade searching for a language of color that could hold feeling without noise. In this painting he found it. The girl sits in a chair that leans inward, forming a small sanctuary. The palette is reduced but luminous. Yellow folds into white. White holds the line. The world outside seems irrelevant. It is a portrait of inwardness. A private life unfolding without expectation.

There is no dramatic backstory to its creation. No manifesto. Matisse painted it because he believed the quiet rooms we inhabit say as much about us as the oceans we cross. After years of upheaval, he valued the silence that follows catastrophe. The painting is a meditation on attention.

Its disappearance, however, was anything but quiet.

The Heist

In October 2012, a group of thieves entered the Kunsthal Museum in Rotterdam before dawn. It was one of the quickest museum heists in modern history. The security system malfunctioned. The building had no night guards. In minutes, seven paintings were removed from the walls, slipped out a door, and taken into the night. Among them was Reading Girl in White and Yellow.

The story grew stranger as months passed. Romanian police later arrested several suspects. In the aftermath, one woman confessed that the stolen paintings had been burned in a stove to destroy evidence. Forensic traces of pigments and nails were reportedly found in the ashes. Whether every detail of that confession is true remains uncertain, but most experts believe the painting no longer exists. A moment of silence, gone in flame.

Why this painting is part of Ghosts of the Ice

While Rembrandt’s painting stormed with chaos and Klimt’s explored the vastness of human meaning, Matisse’s vanished girl operates in another register. She is not grappling with the heavens. She is not caught in a cosmic cycle. She is simply reading. And yet simplicity is often the first casualty of loss. The Arctic understands this better than anyone. The ice disappears quietly. Not with fire or theft or scandal. But with warmth. With the thinning of a season. With the softest melt you can imagine.

This painting’s disappearance is not loud. It is domestic, almost intimate. But that is precisely why it belongs in Ghosts of the Ice. It reminds us that what vanishes is not always heroic or monumental. Sometimes it is the small room, the quiet voice, the moment of focus that slips away first. The things we assume will always be there.

A different kind of ending

I am not predicting what will happen in the Arctic because the truth is no one knows. The sea decides. The weather decides. The people aboard the ship, each with their own map of intentions, will find what they find. And perhaps that uncertainty is the closest connection to Reading Girl in White and Yellow. The girl in the painting existed in a moment she did not expect to be anything other than ordinary. Then it vanished. The page she was reading is unreadable now.

My reinterpretation of the painting will use thermochromic pigments, shifting gently with temperature. Her outline may soften. Her colors may fade. Parts may disappear and then return. In place of narrative, there will be quiet transformation.

This is not an imitation of loss. It is an attempt to understand it.

In my next blog, I’ll turn from the paintings themselves to the strange machinery that will hold them. The heated frames. The hidden wires. The gentle rise of temperature that makes color retreat and return. It is the part of this project that feels closest to a science experiment, and closest to a metaphor, a frame that behaves like the climate, revealing what disappears when warmth enters the room.

“I do not literally paint that table, but the emotion it produces upon me.”