Entry Thirteen: When I Finally Understood What Was Disappearing

I grew up in Austria. In the winters of the 1980s and 90s, my cousins, friends and I spent every free moment on frozen ponds. Dawn to dusk. Our blades sharpened, breath steaming in the cold morning, laughter echoing across ice that crackled under skates and sticks. We carried a thermos of tea and a sandwich, but mostly we carried energy and hope, hours that felt fun and endless.

I remember those winter afternoons most clearly: the sky turning that pale rose-gold as the sun sank behind distant ridges. Light slipping across the frozen surface, glinting on the frost, then deepening into dusk. The air smelled of pines and wood smoke. The ice would groan, crack, sometimes sing, like the world declaring itself alive, fragile, and full of history under our blades.

Every year at Christmas the world outside would be white. Blanketed in snow. In 1985, 1986, 1987, every year like that. I never worried that any winter could end. I never thought the ice might vanish.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, things began to change. Winters grew milder. Snow became patchy; the ponds froze later, melted sooner. By the 2010s, “white Christmas” was more dream than expectation. I remember the hollow feeling, not dramatic, but quiet, like stepping into a room you half-remember.

Then in December 2019 — almost thirty years after our childhood ice-hockey days, something unexpected happened: I got a call from my friend Alex. “The ponds are frozen,” he said. “Markus Ernst and Andy are in town. Everyone wants to play. Are you in?”

No hesitation. We drove up to the old pond named “Treimischerteich” around noon. The air was cold, clean. The ice glowed under a faint frost. The world felt thinner, quieter. But for a moment, just one afternoon, we found it again. I stepped onto the ice and looked down. I could see through it. Clear as glass. Beneath, the dark water waiting. Around, the trees leaning in, waiting for the music of skates. The sky had that winter afternoon light of my childhood. The smell of winter, smoke and earth.

It was magical. But also sad. Because I knew it might be the last time, the last time I’d skate across that surface, the last crack, the last creak. I knew I was returning to a memory I could hold only in my bones.

That day, I felt something shift. Not just in me, but in memory itself. The ice could die. The winters could disappear. The things I once took for granted, permanence, frost, snow, could vanish.

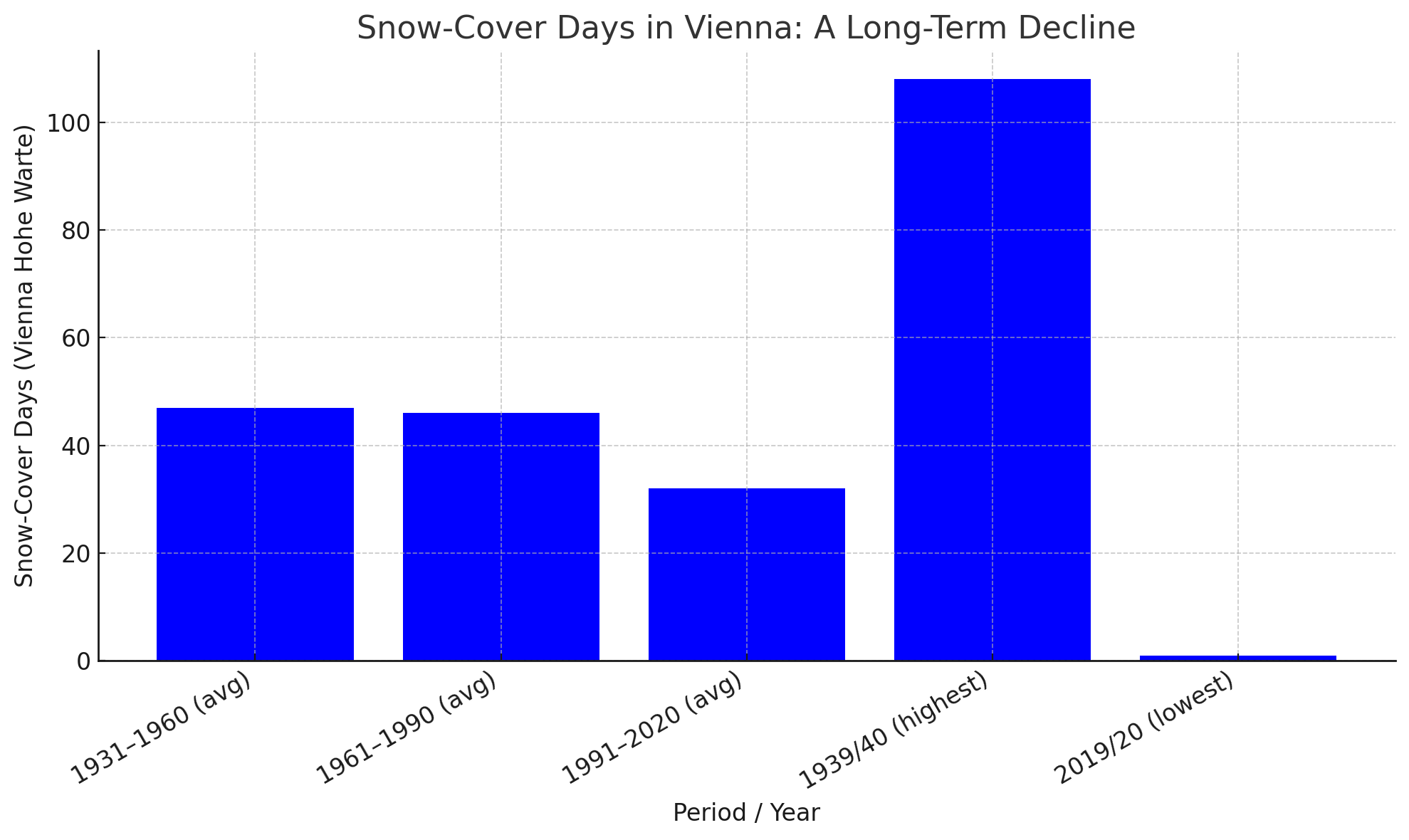

I did not know much about climate data then. I simply felt the vanishing. But later I learned: the feelings were not illusions.

A recent report from the Austrian Alpine Club (ÖAV) warns that most glaciers in Austria are shrinking rapidly, in 2023 alone, 92 of 93 measured glaciers lost length. Only one remained stable. That same year, the country’s largest glacier, the Pasterze, retreated by over 203 metres, a record loss. Data from decades of measurements show consistent decline. Over the last century, the glaciers that once felt eternal have lost volume and area drastically. Some experts now warn that large parts of the Alps may become largely ice-free within forty to fifty years.

It hit me then that my childhood was already part of another time. That the ice I skated on, the winter I took for granted, they weren’t timeless. They were fragile, contingent. They carried history.

That afternoon in 2019, our final skate, became a hinge for me. A moment I carry into Ghosts of the Ice. Because painting lost masterpieces is not simply about memory or art. It is about fragility. About eras ending quietly. About the small vanishings that escape maps but haunt the earth.

Just as in the Arctic, back home the disappearance is already happening beneath our feet. Ponds and Lakes I once trusted to freeze no longer freeze. Climates shift. Ice retreats. Glaciers shrink. Years press forward.

If I felt sorrow skating that last thin ice, I felt something deeper after reading the facts. Not anger. Not despair. But a quiet resolve. To remember what was. To show what is, not just through paintings, but through witnessing. Through art that does not just depict loss, but becomes its echo.

I think that is the first time I truly felt ice vanish. Not as a news headline. Not as a statistic. But as a childhood slipping out from memory, a pond turning black under my feet, a winter breaking.

And because of that afternoon, I paint these ghosts. I paint absence. I paint what the world used to trust but no longer can. I paint so someone, somewhere, may notice what we missed.

“We do not inherit the earth from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children.”